One of the first things you notice about New Zealand wildlife is a distinct lack of mammary glands. The only native land mammals are bats, and I’ve never seen one. They were apparently common in the nineteenth century, but now they’re almost extinct. Blame nasty humans cutting down trees and introducing foreign predators like rats and cats – although my cat would never be clever enough to catch a bat. Do cats eat bats?

One of the first things you notice about New Zealand wildlife is a distinct lack of mammary glands. The only native land mammals are bats, and I’ve never seen one. They were apparently common in the nineteenth century, but now they’re almost extinct. Blame nasty humans cutting down trees and introducing foreign predators like rats and cats – although my cat would never be clever enough to catch a bat. Do cats eat bats?

The Maori name for the bats is pekapeka. They’re really tiny – barely bigger than your thumb – and can be found in very few places. One such place is Tongariro National Park, in the central North Island. There are three Department of Conservation managed campsites around the park, so finding cheap accommodation is easy if you hire a campervan. Obviously the bats only come out at night, so there’s another good reason for sleeping out in the wilderness.

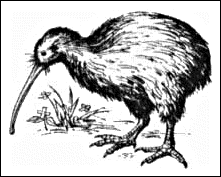

Another native New Zealand creature that only comes out at night is the kiwi, the country’s most famous and special bird. It can’t fly; evolution has reduced its wings to stumps, hidden beneath feathers that are more like fur. Like the bats, kiwis are endangered and so rarely seen in the wild, but there are plenty of places throughout New Zealand where you can see them in captivity, such as Auckland Zoo. I saw a couple of kiwis mating there once. They looked like two tribbles (from Star Trek) stacked one on top of the other. I had to stop myself laughing, especially when a small child standing next to me exclaimed, “Mum, look, that one’s jumping on the other one’s back!”

Another native New Zealand creature that only comes out at night is the kiwi, the country’s most famous and special bird. It can’t fly; evolution has reduced its wings to stumps, hidden beneath feathers that are more like fur. Like the bats, kiwis are endangered and so rarely seen in the wild, but there are plenty of places throughout New Zealand where you can see them in captivity, such as Auckland Zoo. I saw a couple of kiwis mating there once. They looked like two tribbles (from Star Trek) stacked one on top of the other. I had to stop myself laughing, especially when a small child standing next to me exclaimed, “Mum, look, that one’s jumping on the other one’s back!”

Kiwis, scientists have found, are closely related to emus, but not to ostriches. There was a New Zealand bird closely related to the ostrich, but it was hunted to extinction by the Maori long before Europeans arrived in New Zealand with their foreign predators. It was called the moa, and it was huge. I remember the skeleton in Auckland Museum – some species could reach a height of over three-and-a-half metres, more like dinosaurs than birds! The only animals big enough to take them down (before the blundering arrival of human beings) were Haast’s eagles.

No, they weren’t eagles owned by some guy named Haast – he was just the first European to describe them. They’d been extinct for centuries by this point, but they must have been terrifying creatures to behold. They were the largest birds of prey ever known to have existed, and may well have hunted humans together with moas. Maori legend speaks of a monstrous, man-eating bird. Did Haast’s eagles snatch children and carry them off to their nests to devour them? It’s a scary thought.

New Zealand no longer has any particularly dangerous animals. Someone was killed by a shark off the West Coast of the North Island recently, but things like that don’t happen very often. There have only been about a dozen deaths by shark in New Zealand in the last two hundred years. Australia’s the death-trap. New Zealand doesn’t have any killer spiders, (although the weta can give you a painful nip,) or any deadly snakes – in fact it doesn’t have any snakes at all. It has a few other reptiles, though: frogs, geckos, skinks and, most importantly, the tuatara.

Like practically every other native New Zealand specie, the tuatara is endangered. Most people think it’s a lizard, but it actually belongs to a far older family, older than most dinosaurs, of which it’s the only surviving example. It has a lower body temperature than any other type of reptile and can live well over a hundred years. Unfortunately, it’s nearly impossible to see a tuatara in the wild, as they can only live in areas devoid of rats, which pretty much limits them to a handful of sanctuary islands that tourists aren’t allowed to trample on. I’ve seen one at Auckland Zoo, though, and, to be honest, it was rather boring compared to the mating kiwis!

Like practically every other native New Zealand specie, the tuatara is endangered. Most people think it’s a lizard, but it actually belongs to a far older family, older than most dinosaurs, of which it’s the only surviving example. It has a lower body temperature than any other type of reptile and can live well over a hundred years. Unfortunately, it’s nearly impossible to see a tuatara in the wild, as they can only live in areas devoid of rats, which pretty much limits them to a handful of sanctuary islands that tourists aren’t allowed to trample on. I’ve seen one at Auckland Zoo, though, and, to be honest, it was rather boring compared to the mating kiwis!

Not all New Zealand animals are so elusive. There are eels in the estuary, pukekos in park, and a whole array of native birds in most people’s back gardens. I’ve often gone to sleep hearing the sweet yet haunting howls of the onomatopoeically named morepork, an incredibly cute little brown owl, and woken up in the morning to the idyllic tune of a tui. My parents get lots of silvereyes in the tree outside their kitchen window, and it’s always entertaining to watch the fantails flitting about the lawn, flicking their tail feathers.

An absolutely incredible place to go to observe native New Zealand birds in their natural habitat is the visitor-friendly island sanctuary of Tiritiri Matangi. You can take a ferry there from either downtown Auckland or Gulf Harbour, but Gulf Harbour’s cheaper and has free parking. Make sure you book, though, and make sure you take food with you, along with sunscreen, a hat, a raincoat, comfortable walking shoes, binoculars and – if the weather looks particularly nice – swim stuff. You’ll be doing a lot of bush trekking, and it’s nice to jump in the sea afterwards. There are lots of little blue penguins around the shore of the island. If you’re lucky, you’ll even see them in their nesting boxes.

An absolutely incredible place to go to observe native New Zealand birds in their natural habitat is the visitor-friendly island sanctuary of Tiritiri Matangi. You can take a ferry there from either downtown Auckland or Gulf Harbour, but Gulf Harbour’s cheaper and has free parking. Make sure you book, though, and make sure you take food with you, along with sunscreen, a hat, a raincoat, comfortable walking shoes, binoculars and – if the weather looks particularly nice – swim stuff. You’ll be doing a lot of bush trekking, and it’s nice to jump in the sea afterwards. There are lots of little blue penguins around the shore of the island. If you’re lucky, you’ll even see them in their nesting boxes.

Tiritiri Matangi is a very special island, because it is free of predators such as the possum, which will eat the eggs and chicks of endangered native birds. Possums were stupidly introduced to New Zealand from Australia, and since then they have become hated to the extent that kiwis, (the people of New Zealand, not the tribble-like birds,) will deliberately try to run them over. Their one redeeming feature is their fur… so soft… but as soon as I moved to New Zealand, I had it drummed into me that possums are the spawn of Satan.

So, not having any predators to fear, the birds of Tiritiri Matangi have become bold around the island’s human visitors. One particular bird, a now-deceased giant takahe called Greg, became so bold that, for a time, I referred to the island as Jurassic Park. Takahe are like huge, blue chickens with big, red beaks. They can’t fly, but – Jeez – can they run! A few years ago, Greg chased me and my friends across half the island. When we stopped, it snapped at the bottoms of my shorts and kept leaping up to my crotch. I remember running for ages and, panting, stopping to look behind.

So, not having any predators to fear, the birds of Tiritiri Matangi have become bold around the island’s human visitors. One particular bird, a now-deceased giant takahe called Greg, became so bold that, for a time, I referred to the island as Jurassic Park. Takahe are like huge, blue chickens with big, red beaks. They can’t fly, but – Jeez – can they run! A few years ago, Greg chased me and my friends across half the island. When we stopped, it snapped at the bottoms of my shorts and kept leaping up to my crotch. I remember running for ages and, panting, stopping to look behind.

“I think we lost it,” I said.

Then it appeared over the crest of the hill, wings outstretched, legs working like the clappers, beak pointing straight at us!

But encountering nature in New Zealand isn’t usually as invigorating as that. The coast is a great place to head to see wildlife, and it begins to get more mammalian. New Zealand fur seals can be observed on many rocky shores around the country, such as the Otago Peninsula. My family went there while on our South Island campervan tour. It’s a Mecca for wildlife, including a magnificent colony of albatrosses. The very best wildlife encounter I’ve had in New Zealand, however, was just off the coast of Auckland.

There are a number of companies that take tourists out on ferries to see dolphins, and the tourists are rarely disappointed. My family and I have been on several of these dolphin trips and we’ve never had a no-show. Whole pods of dolphins come right up to the boat and play in the waves around it, leaping, diving and engaging in light sexual activity.

Once, I was sitting at the front of the ferry with my legs dangling over the edge. One of the dolphins rose from the sea and tapped my foot in a clearly playful way – so awesome! We even got to swim with the dolphins, although, for me, this turned into a rather traumatising experience.

Swimming with dolphins is an activity that tops bucket lists around the world. It’s known as an experience so peaceful and happy it can cure depression, bringing people back to nature and generally being as wonderful as a field of unicorns vomiting rainbows. For me, alas… I got into the water and swam around a bit. None of the dolphins seemed to want to say hello. Then I felt lots of small, solid things knocking into my body, up my arms and legs. I suddenly realised the water was pink, and I was floating in the centre of a massacre: pink chunks of dead fish. Being a squeamish teenage girl (and unashamed ichthyophobe,) I screamed and swam back to the boat, taunted by the laughter of my family.

Swimming with dolphins is an activity that tops bucket lists around the world. It’s known as an experience so peaceful and happy it can cure depression, bringing people back to nature and generally being as wonderful as a field of unicorns vomiting rainbows. For me, alas… I got into the water and swam around a bit. None of the dolphins seemed to want to say hello. Then I felt lots of small, solid things knocking into my body, up my arms and legs. I suddenly realised the water was pink, and I was floating in the centre of a massacre: pink chunks of dead fish. Being a squeamish teenage girl (and unashamed ichthyophobe,) I screamed and swam back to the boat, taunted by the laughter of my family.

The day might have been ruined, were it not for the whale. Typical me, though, I was facing the other way when its head came vertically out of the water. My mum tells me it was fantastic. But more amazing still were the gannets.

The sky was thick with them. They came because they saw the dolphins. Gannets have learned that their hunting technique compliments the dolphins’ perfectly. The dolphins gather deep down in the ocean, underneath a school of fish, and drive the fish upwards, trapping them at the surface – where the gannets can descend upon them from the sky. They dive into the waves like golden-headed missiles, so sharp and graceful… The whole boat was transfixed.

You can see a very impressive colony of gannets at Muriwai Beach, (which, coincidentally, is where that guy was killed by a shark,) just a short drive from Auckland City. I’d well recommend it – they’re absolutely beautiful birds – but seeing them out on the ocean, working together with a pod of dolphins, is a wildlife experience I’ll never forget.

Article by Abigail Simpson, author of POMS AWAY! A British Immigrant’s View of New Zealand